This blog and our recent fact sheet provide reasons to regulate the use of nicotine salts in e-cigarettes/vaping products.

Nicotine salts are recognized as a public health threat

As the lawyers for the state of New York put it: "nicotine salts, produce an easier-to-inhale aerosol that is not only more palatable than the smoke produced from a combustible cigarette, but also causes less throat irritation. Thus, a consumer ingests more nicotine from a JUUL pod with less discomfort than one would experience when smoking a combustible cigarette."

It's not only lawyers who are concerned when companies alter the nicotine molecule to make it easier to inhale. Last fall, the former head of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, David Kessler, identified nicotine salts as one reason that e-cigarettes should not be permitted on the market in the USA. Researchers have identified this manufacturing technique as the start of a "nicotine arms race" that puts a generation of youth at risk by making e-cigarettes more palatable and "vastly more addictive for never-smokers".

Last month the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health identified controls on nicotine salts among measures that the federal government should consider.

Why nicotine salts are easier to inhale than freebase nicotine

Nicotine, as extracted from tobacco or created synthetically, is a base (pH greater than 7). In this form, it is sometimes called freebase nicotine. Freebase nicotine - like that found in the smoke of cigars or pipes - is harsh to the taste and hard to inhale.

Exposing freebase nicotine to an acid converts the nicotine to a salted form. (Chemically speaking, a salt is a substance that is produced by the reaction of an acid with a base.) The nicotine molecule picks up a hydrogen proton, making it similar to the protonated nicotine found in cigarette smoke. This form has lower pH and produces a smoother sensation when being inhaled. It is less bitter and more palatable.

E-cigarette companies treat nicotine with an organic acid to produce nicotine salts. JUUL uses benzoic acid; Vype uses lactic acid. Other brands use levulinic acid, or a combination of organic acids.

E-cigarettes that are not treated with organic acids to create nicotine salts would have a pH of about 7.5-8.0. Like cigars, they would be harsh to the taste and hard to inhale.

|

| Slide courtesty of Dr. Arit Harvanko, UCSF "It's about a billion lives" - January 31, 2020 |

No denying the purpose of nicotine salts is to facilitate inhalation and absorption

E-cigarette manufacturers have been open about the way that nicotine salts make it easier to inhale and absorb nicotine. In their patent application, JUUL's inventors identified that this formulation "facilitates adminsitration of nicotine to an organism (e.g., lung)".

JTI-Macdonald informs Canadian customers that the nicotine salts in its Logic Compact uses "may make it easier to inhale the level of nicotine contained in the product than would be possible without it."

Regulating additives that increase addictiveness, attractiveness and palatability.

For many years, regulators have recognized the need to address the use of additives in tobacco products which increase the attractiveness and addictiveness of the products. Before e-cigarettes were a regulatory concern, governments which signed the global tobacco treaty (the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control) recommended that they should all “regulate, by prohibiting or restricting, ingredients that may be used to increase palatability in tobacco products.” In 2005, they identified the need to develop regulations to reduce the attractiveness and addictiveness of products, without yet agreeing on a way to do so.

The European Union set out to fill this void and appointed a panel of experts to report on the “Addictiveness and Attractiveness of Tobacco Additives.” Their 2010 report predated e-cigarettes, but concluded that “additives that facilitate deeper inhalation… may enhance the addictiveness of nicotine indirectly,” and that additives that increased attractiveness could result in “decreasing the harshness of the smoke, and inducing a pleasant experience of smoking.”.

When the European Union Directive on tobacco was revised in 2014 to include e-cigarettes, it required all EU governments to ban cigarette additives "that facilitate inhalation or nicotine uptake.” Some governments have also banned such additives in e-cigarettes: France, for example, prohibits manufacturers of e-cigarettes using “des additifs qui facilitent l’inhalation ou l’absorption de nicotine," and Iceland similarly bans e-cigarette "substances that facilitate the inhalation or uptake of nicotine." Such measures are also in place in Hungary

These laws, however, do not seem to have prevented the sale of nicotine salts. Salted nicotine liquids are sold through BAT's web-sites in France and Hungary.

Regulating e-cigarette additives in Canada

Canada takes a different approach towards additives than does the European Union. Where as the EU bans additives on the basis of their impact, Canada bans them on the basis of their chemical properties.

Currently, nine categories of ingredients are prohibited in Canadian e-cigarettes. These are: amino acids, Caffeine, colouring agents, essential fatty acids, glucuonolactone, probiotics, taurine, vitamins and mineral nutrients.

Nicotine salts were introduced in Canada a few months after this law was passed. Before August 2018 (when JUUL began marketing in Canada) the other pod-based systems were selling freebase nicotine products with nicotine levels no greater than 18 mg/ml.

Soon after, the other manufacturers of pod-systems followed suit. Imperial Tobacco changed its marketing plans and introduced a re-designed pod-system with nicotine salts in January 2019. Within weeks, each of the four large tobacco multinationals had JUUL or copy-cat products on the market. Sales of Imperial Brands Myblu were expanded across Canada in January and Japan Tobacco's Logic was introduced in February 2019.

In a matter of months, manufacturers changed the Canadian market place in ways which almost certainly have contributed to the increase in youth nicotine use.

A simple fix may be available to roll the clock back: By amending the list of prohibited ingredients to ban all acids, and not just amino acids, manufacturers would no longer be able to sell vaping liquids made with nicotine salts.

JTI-Macdonald informs Canadian customers that the nicotine salts in its Logic Compact uses "may make it easier to inhale the level of nicotine contained in the product than would be possible without it."

Regulating additives that increase addictiveness, attractiveness and palatability.

For many years, regulators have recognized the need to address the use of additives in tobacco products which increase the attractiveness and addictiveness of the products. Before e-cigarettes were a regulatory concern, governments which signed the global tobacco treaty (the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control) recommended that they should all “regulate, by prohibiting or restricting, ingredients that may be used to increase palatability in tobacco products.” In 2005, they identified the need to develop regulations to reduce the attractiveness and addictiveness of products, without yet agreeing on a way to do so.

The European Union set out to fill this void and appointed a panel of experts to report on the “Addictiveness and Attractiveness of Tobacco Additives.” Their 2010 report predated e-cigarettes, but concluded that “additives that facilitate deeper inhalation… may enhance the addictiveness of nicotine indirectly,” and that additives that increased attractiveness could result in “decreasing the harshness of the smoke, and inducing a pleasant experience of smoking.”.

When the European Union Directive on tobacco was revised in 2014 to include e-cigarettes, it required all EU governments to ban cigarette additives "that facilitate inhalation or nicotine uptake.” Some governments have also banned such additives in e-cigarettes: France, for example, prohibits manufacturers of e-cigarettes using “des additifs qui facilitent l’inhalation ou l’absorption de nicotine," and Iceland similarly bans e-cigarette "substances that facilitate the inhalation or uptake of nicotine." Such measures are also in place in Hungary

These laws, however, do not seem to have prevented the sale of nicotine salts. Salted nicotine liquids are sold through BAT's web-sites in France and Hungary.

Regulating e-cigarette additives in Canada

Canada takes a different approach towards additives than does the European Union. Where as the EU bans additives on the basis of their impact, Canada bans them on the basis of their chemical properties.

|

| Prohibited E-cigarette ingredients Canadian Tobacco and Vaping Products Act |

Nicotine salts were introduced in Canada a few months after this law was passed. Before August 2018 (when JUUL began marketing in Canada) the other pod-based systems were selling freebase nicotine products with nicotine levels no greater than 18 mg/ml.

Soon after, the other manufacturers of pod-systems followed suit. Imperial Tobacco changed its marketing plans and introduced a re-designed pod-system with nicotine salts in January 2019. Within weeks, each of the four large tobacco multinationals had JUUL or copy-cat products on the market. Sales of Imperial Brands Myblu were expanded across Canada in January and Japan Tobacco's Logic was introduced in February 2019.

In a matter of months, manufacturers changed the Canadian market place in ways which almost certainly have contributed to the increase in youth nicotine use.

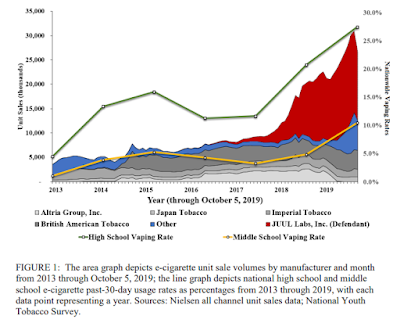

A simple fix may be available to roll the clock back: By amending the list of prohibited ingredients to ban all acids, and not just amino acids, manufacturers would no longer be able to sell vaping liquids made with nicotine salts.