Three months ago,

Statistics Canada released some results from the Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey (CTNS) This is a one-time survey conducted between the end of October and mid-December in 2019. The survey was taken by 8,600 Canadians, fewer than half of those who were asked to do so (a reponse rate of 44%).

Statistics Canada developed the survey with Health Canada, setting

the survey goals to

"fill important data gaps related to vaping, cannabis, and tobacco usage" and to

"inform policy and provide a current snapshot of use across Canada."

The

first results of the CNTS were released by Statistics Canada on March 5. These focused on:

* who was vaping (15% of youth and young adults, but less than 3% of adults);

* what they were vaping (nine times out of ten it was nicotine);

* why they were vaping (kids for fun, adults as a way to quit cigarettes); and

* what they thought about the harms of vaping (opinions varied).

Because this survey is not formally connected to other surveillance tools, drawing comparisons with previously estimated rates of smoking or vaping are problematic. Nonetheless,

as we wrote in March, it seems clear that the expansion of vaping marketing has had a more profound impact on youth and young adults than it has had on adult smokers. The number of young vapers has increased greatly, while the use of vaping products by adult smokers seems to have not changed measurably.

In late May, Statistics Canada generously provided us with the Public Use Microfile for this survey, allowing us to extract information on some key aspects of vaping behaviour among Canadians in 2019.

1. One-fifth of Canadian vapers are teenagers who have never smoked a whole cigarette.

The survey results show that the number of Canadians who have never smoked cigarettes but who have used e-cigarettes in the past month exceed those who have once smoked but are now vaping instead. This is particularly true for teenagers, where three-quarters of vapers have never smoked a cigarette.

Last fall there were about 1.46 million Canadians who had vaped in the past month. Of these, one-quarter (364,800) were "former smokers." The remainder, in roughly equal quantity, were "never smokers"(535,900) or "current smokers" (559,700 dual users).

|

Past month vapers by age and smoking status

Statistics Canada.

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2019 |

2. For every 100 people who tried vaping, 13 became daily users. A great accomplishment for tobacco control has been establishing an environment where young people do not try smoking cigarettes -- even once. CTNS data reflects that progress: Four-fifths of young people (15 to 24 years of age) reply "no" to the question "Have you ever smoked a whole cigarette," compared with fewer than one-half of those in previous generations (over 25 years of age).

But among those who have ever smoked a cigarette, the proportion who became daily (likely addicted) smokers is the same at every age . Almost one in five (18%) of those who ever smoked a whole cigarette were smoking daily, regardless of their age group. This speaks to the addictive power of cigarettes and nicotine.

For vaping, more than one in eight (13%) of those who ever tried vaping were doing it every day last fall. In this case, however, the pattern is reversed in comparison with smoking. In this case, it is the younger generation who had much higher rates of experimentation than older Canadians. Fewer than one-fifth of adults (16%) had ever tried vaping, compared with more than two-fifths of youth and young adults (41%).

For cannabis, the rate of experimentation was essentially the same for all age groups, although young people were more likely to be daily users. Overall, the rate of daily use was about 9%, consistent with other estimates of rates of addiction to cannabis.

|

Population prevalence of ever trying product and percentage of those who were daily users

Statistics Canada.

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2019 |

3. Almost half of smokers made a quit attempt over the past year. Few used a recommended cessation aid.

Smokers and former smokers who said they had quit in the past year were asked how many times they had stopped smoking for at least one day as part of a quit attempt, and were also asked whether they had used any specific quit methods.

Almost one half (45%) identified making at least one quit attempt, with almost one-third (31%) trying more than twice.

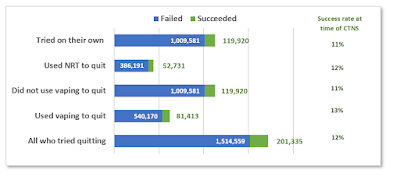

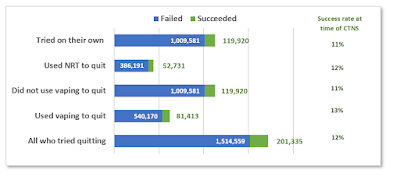

When asked whether they had tried to quit using specific approaches, the majority (70%) said they had tried to quit on their own, and half (54%) said they had tried reducing the number of cigarettes. One-third (35%) said they had switched to vaping, one-quarter (25%) said they had used nicotine replacement and one-fifth (20%) said they had used an "other" method. (Because prescription medication was not identified on the questionnaire, treatments like varenicline may be included under "other"). So few people reported using Quitlines or internet programs that the number is unreportable.

The vast majority (88%) of these quit attempts were unsuccessful. Of the 1.75 million Canadians who tried to quit, only 201,000 were still not smoking at the time of the survey (12%). Differences in the outcomes for those using different cessation approaches were not tested for statistical significance, but are presented below. The largest number of successful quitters were those who identified as using no quit method.

The CTNS also asked current vapers whether they had tried quitting vaping, but is designed only to show how many tried but failed to quit. One-in-three vapers (35%) had tried at least once in the past year, but were still vaping at the time of the survey. This included 30% of those who vaped on a daily basis.

|

Methods used by those who tried to quit smoking in past year

Statistics Canada. Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2019 |

4. Tobacco-flavour is the only vaping flavour not attracting young people to vape.

Those who vaped in the past month were asked what their main reason for vaping was and also which flavours they usually chose.

Four in ten vapers (39%) give recreational reasons for vaping, saying that the main reason they vape is out of curiosity or because they enjoy it. Tobacco flavours are almost never their usual flavours. The number who made this choice is too small to be reported according to Statistics Canada's guidelines. More than one-half of this group (56%) choose fruit, dessert or candy flavours, and about one-seventh (16%) say they prefer menthol or mint flavours. One-quarter (24%) do not have a usual flavour or have one different than those listed.

Four in ten vapers (37%) give health-related reasons for vaping, saying the main reason they vape is to quit smoking, to cut down on the number of cigarettes they smoke or to avoid returning to smoking. Among this group, one-quarter (26%) used tobacco flavours. One-fifth (20%) choose mint or menthol flavours and twice as many (41%) choose fruit, desert or candy flavours.

These differences were not tested for statistical significance, but are presented below.

|

Flavour preferences by main reason for vaping

Statistics Canada.

Canadian Tobacco and Nicotine Survey, 2019 |

This information is available on a

downloadable fact sheet.