While the federal government plans to reduce the use of these plastic products (and eventually also to reduce the use of other food services packages and drink cups), its intentions for tobacco waste are limited to increasing the frequency that these products are recycled or recovered.

The exclusion of tobacco-waste from the proposed ban on single-use plastics is surprising in some ways:

- Cigarette butts have been identified as a much more frequent waste problem than plastic straws or carrier bags. In the most recent Greats Canadian Shoreline Cleanup, cigarette butts far exceeded other plastic waste.

- Parliamentarians studying the problem of plastic waste recommended that cigarette butts be included in a ban of harmful single-use products.

- The scientific review conducted to support the federal strategy identified cigarette butts as a leading source of discarded plastic.

- Cigarette butts do not biodegrade, but continue to leach toxic amounts of nicotine, pesticides, polycyclic aromatichydrocarbons, arsenic, and heavy metals such as lead and cadmium.

- E-cigarette waste has been labelled as hazardous waste by U.S. environmental and health agencies.

Continued exceptionalism for the tobacco industry?

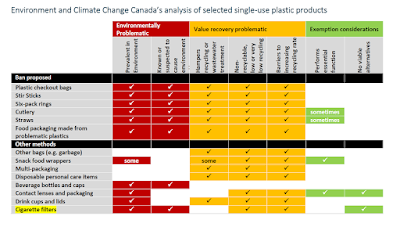

It has long been observed that tobacco manufacturers are frequently exempted from regulations that are applied to other industries. In the case of the federal plastics strategy, Environment and Climate Change Canada has made clear the reasons it is exempting cigarette filters from its ban on single use plastics.

The department established 3 criteria to decide which single-use plastics to ban: 1) whether they were found in the environment, 2) whether they were often not recycled and 3) whether they have readily available alternatives.

It was the department's determination that there are no alternatives to cigarette filters that seems to underpin their decision to implement measures to mitigate the problems caused by post-consumer tobacco and vaping waste, but not to end the use of these harmful plastics.

The world is moving to banning single use plastics, and the tobacco industry is trying to avoid that impact.

Measures to curb the use of single use plastics are under development in many countries. Last year, the European Union adopted a directive requiring its member states to pass legislation by July 2021 to require tobacco manufacturers to cover the costs of awareness-raising, litter clean-up, data gathering and reporting and waste collection, and also to require waste-related markings on tobacco product packaging.

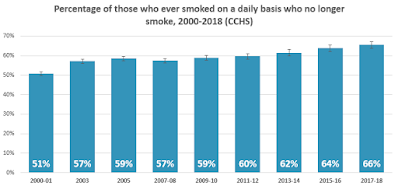

Not surprising then, that tobacco companies have accelerated cross-border activities to frame the issue and to influence public policy in ways that would minimize the impact on their business. They focus attention away from their producer responsibilities and instead present tobacco waste as a problem related to smoker behaviour. They frame tobacco waste as a problem caused by user non-compliance, and not the result of manufacturing practices and product design.

Philip Morris International says its objective is to "Prevent littering of our products by promoting appropriate behaviour among adult consumers.” This year its subsidiary, Rothmans, Benson and Hedges, provided grants to 17 clean-up operations in Canada -- leveraging the work of volunteers to clean up the waste it caused.

British American Tobacco, and its Canadian subsidiary Imperial Tobacco Canada Ltd also promotes measures addressed at consumers, not producers. "BAT acknowledges that cigarette filters provide a waste issue for regulators. However, it believes that the most appropriate solution is promoting the proper disposal of butts so that they don’t pollute the environment."

These corporate initiatives of the companies are worrisome. Good implementation of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control would not permit Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives, like RBH's grants to clean-up squads, nor tobacco industry partnerships, like Imperial Tobacco's former sponsorship of municipal ashtray programs.

The federal government has to date given no signal that it will protect its single use plastics plan from tobacco industry influence. (In its recent roundtable on the topic, the U.K. environment ministry acknowledged these responsibilities.)

Public education is not enough. There are better options to choose from

A number of options for managing tobacco and vaping product waste have been developed by independent researchers and civil society.

In addition to amplifying existing measures (like smoke-free laws, public education and product labelling), these include:

- Banning cigarette filters (or phasing out cigarettes)

Cigarette filters do not reduce the harm of smoking, and they may increase it. There are increasing calls for governments to ban the sale of cigarettes made with filters, a measure which is also supported by leading Canadian environmental groups, including the Environmental Law Centre at the Universityof Victoria, the National Zero Waste Council, and Greenpeace Canada. - Mandatory Deposit-Return

For several years, we have promoted the use of Deposit-Return systems at provincial levels to address cigarette waste. In 2016, the Union of British Columbia Municipalities called for such a system, which was rejected by the provincial government at that time. - Mitigation fees

These can be imposed at the national or sub-national level. San Francisco currently charges retailers $1 per package to clean up tobacco waste.

The widespread presence of ashtrays imply tacit government consent, acceptance and even approval of widespread smoking in public. They strengthen the impression that smoking is common, and create smoking zones in public places. Such re-normalization of smoking is directly aligned with the strongest interests of the tobacco industry.

Governmental responsibilities to address tobacco use include environmental objectives AND the obligation to protect these from tobacco industry interference.

By engaging in the development of federal, provincial and municipal approaches to single-use plastics, health agencies can ensure that these policies support public health objectives. One way to do this is to respond to federal proposals, which are open for comments until December 9, 2020.

A briefing note to assist this process can be found here.