|

| OTRU Webinar: The Population Impact of E-Cigarettes in Canada: A Simulation Model |

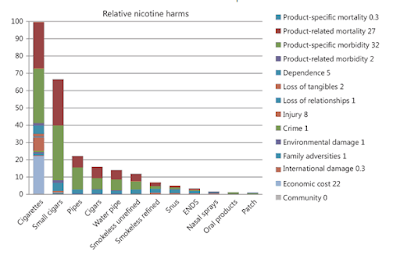

2013: The meeting that decided that e-cigarettes are "95% safer"

It was in July of 2013 that a dozen men met for a two-day workshop in London, England to exchange views on the various forms in which nicotine could be consumed and the harms that were associated with each of those products.Blood Flow: In a 2022 study, Poonam Rao and colleagues (xiv) showed that a wide range of e-cigarettes impaired blood flow (as measured by flow-mediated dilation) in much the same way and to the same degree as combustible cigarettes. E-cigarette aerosol, cigarette smoke and marijuana smoke all impaired blood flow to approximately the same degree. Repeated exposure of arteries to inhaled smoke or e-cigarettes aerosols over many years is a risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease many years later. This study suggests that the cardiovascular disease risks from e-cigarette aerosol would not be less than from cigarette smoke.

"First, avoiding combustion does not remove all noxious chemicals. Although e-cigarettes do not form high levels of strongly carcinogenic benzopyrenes and tobacco-specific nitrosamines, heating mixtures of nicotine and propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin (PG:VG) in e-cigarettes generates reactive carbonyls such as formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acrolein [11, 12, 13, 14], which have been variably linked to carcinogenesis,[15] cardiovascular injury [16, 17], and increased risk of cardiovascular disease [18]. The generation of carbonyls from e-cigarettes varies with use patterns, e-liquid ingredients, and operating conditions [19], and even though the extent of carbonyl generation by e-cigarettes is generally lower than by combustible cigarettes, daily carbonyl exposure from e-cigarettes could still exceed exposure limits [20]. Second, e-cigarette aerosols sporadically contain metals (Fe, Ni, Cu, Cr, Zn, Pb), generated by the heating coil [21], which could add to the toxicity of the aerosol. Third, like combustible cigarettes, e-cigarettes produce aerosols that contain fine and ultrafine particles [22], which can trigger cardiovascular events and promote the progression of pulmonary and cardiovascular disease [23]. Finally, a direct comparison of the relative toxicity of e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes may not be entirely meaningful. Toxicity due to a chemical, drug, or exposure depends upon its dose. Therefore, even though per puff, e-cigarettes may generate lower levels of toxins; their toxicity may approach that of combustible cigarettes if the use of e-cigarettes (exposure/dose) is higher than that of combustible cigarettes. For instance, if e-cigarettes are half as harmful as combustible cigarettes, but are used twice as much, there would be little harm reduction by using e-cigarettes over combustible cigarettes. Therefore, for both e-cigarettes and combustible cigarettes, harm could be reduced only by reducing exposure. Here too, the relationship is not straightforward. The dose response relationship between smoking and ischemic heart disease, for instance, is non-linear. It shows that smoking just 3 cigarettes a day imparts 80% of the harm attributable to smoking 20–40 cigarettes per day [24]. In other words, 85–92% reduction in exposure results in only 20% harm reduction. Therefore, reducing toxin exposure by using e-cigarettes may not result in proportional harm reduction. Indeed, as discussed below, recent evidence suggests that even though e-cigarettes generate lower levels of toxins than combustible cigarettes, their use may be associated with significant cardiorespiratory injury as well as immune dysregulation."

2021: More attempts to put a number on the concept of relative harm

Despite these cautions, and in the face of conflicting estimates, changing product designs and uncertain science, a group of New Zealand researchers nevertheless recently set out to establish a numerical comparison of the risks of smoking and vaping. Their motivation for doing so was ensure that policy makers who were using simulation models to evaluate regulatory options had a numerical estimate of harm to use in these calculations. Their results (Wilson, N et al. Improving on estimates of the potential relative harm to health from using modern ENDS (vaping) compared to tobacco smoking)(xvi) were published last November.

These researchers used bio-marker studies to compare relative harm. They sought to establish equivalencies among e-cigarettes, combustible cigarettes, certain toxic emissions and their known relationship to certain diseases.

In order to reflect the newer designs of products, they looked only at studies based on data collected after 2017. They only found 4 studies that provided the range of data their methods required, and within these studies was a wide range of results. The nature of the exercise meant significant lacunae remained, leading the research team to acknowledged "a high level of uncertainty of the relative harm of ENDS [electronic nicotine delivery systems] use compared to smoking."

With these caveats, they nonetheless produced an overall estimate of relative harm, finding modern e-cigarettes had 33.2% the harm of cigarettes: "This analysis suggests that the use of modern ENDS devices (vaping) could be up to a third as harmful to health as smoking in a high-income country setting."

|

| Wilson et al, 2021 |

(ii) Public Health England. Vaping in England: evidence update. 2015.

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00042-2/fulltext

https://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/human-lungs-are-created-to-breathe-clean-air-the-questionable-quantification-of-vaping-safety-95-less-harmful

https://www.sanidad.gob.es/ciudadanos/proteccionSalud/tabaco/docs/InformeCigarrilloselectronicos.pdf

(xii) Gotts J E, Jordt S, McConnell R, Tarran R. What are the respiratory effects of e-cigarettes? BMJ 2019; 366 :l5275 doi:10.1136/bmj.l5275.

(xiii) Nicholas D Buchanan, Jacob A Grimmer, Vineeta Tanwar, Neill Schwieterman, Peter J Mohler, Loren E Wold, Cardiovascular risk of electronic cigarettes: a review of preclinical and clinical studies, Cardiovascular Research, Volume 116, Issue 1, 1 January 2020, Pages 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvz256.

(xiv) Poonam Rao, MBBS, Daniel D Han, BA, Kelly Tan, Leila Mohammadi, MD, PhD, Ronak Derakhshandeh, MSc, Mina Navabzadeh, PharmD, Natasha Goyal, MD, Matthew L Springer, PhD, Comparable Impairment of Vascular Endothelial Function by a Wide Range of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Devices, Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2022;, ntac019, https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntac019.

(xvi) Wilson, N., Summers, J.A., Ait Ouakrim, D. et al. Improving on estimates of the potential relative harm to health from using modern ENDS (vaping) compared to tobacco smoking. BMC Public Health 21, 2038 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-12103-x.