This blog provides an update on these two sets of events.

States representing more than one-third of U.S. citizens have filed suits against JUUL

At least nine state-level governments have filed suits against JUUL: Arizona, California, Illinois, Massachussets, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Washington DC.

The state attorneys general which have filed these suits are using their powers and responsibilities under state-level consumer protection laws, other laws designed to address wrongful behaviour by organizations (i.e. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act), or state level restrictions on tobacco sales.

Their lawsuits claim that JUUL broke these laws in multiple ways. These include the design of their products, the targetting of young people in advertising, the misrepresentation of the risks of their products including by understating the amount of nicotine, the failure to meet the special duty of their publicly stated corporate objectives, the sale of defective products, their negligence behaviour and by other means.

In addition to asking the courts to order JUUL to pay fines, the states are also asking for court orders to stop certain marketing practices. The specific requests vary by lawsuit, but include a request for a ban on the sale of JUUL devices, a maximum level of nicotine of 20 mg/ml, a ban on free distribution of products and the use of social media. Some lawsuits are asking that JUUL to be required to contribute to the costs of cleaning up the problems it has caused by contributing to cessation programming.

In short, courts in these states are being asked to do what state legislators are unable to do under the U.S. legal system -- curb the marketing of vaping devices. Faced with a problem that their federal government is not addressing, state governments are seeking alternative ways to protect the health of their young citizens by reaching out to another branch of government for help.

In filing the suits, these law officials have provided excellent and readable summaries of JUUL's practices over recent years. The Pennsylvania claim, for example, provides a concise but comprehensive review of concerns with those products, as well as a compilation of key documents.

Why single out JUUL?

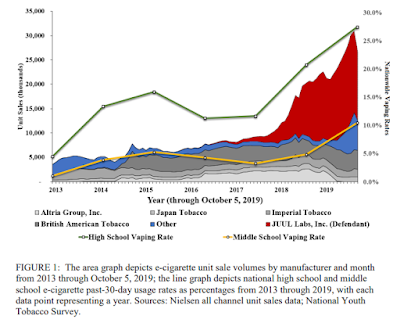

While the sales of products by other companies was relatively stable over most of the decade, it was the accelerated marketing of JUUL after 2017 that is associated with the growth in the market and also the growth in youth use, as shown in a figure from the Pennsylvania claim.

In the U.S. the singling out of JUUL is more obvious than it might be in Canada, where the behaviour of JUUL-imitators (like VYPE, STLTH, LOGIC, BLU) are seemingly no less problematic.

Meanwhile, in Canada

There are historic examples of Canadian governments and citizens using consumer protection laws to challenge tobacco industry marketing practices.

Tobacco:

Following a forceful complaint by the Non-Smokers' Rights Association in 2003, the federal Competition Bureau took enforcement action against the three major cigarette manufacturers. This resulted in an agreement in 2006 that those companies would stop using the terms light and mild, and an agreement was reached the following year with smaller companies operating in Canada. In 2011, Health Canada put regulations into place under the federal Tobacco Act to prohibit the use of the terms light and mild.

A class action (Knight vs. Imperial Tobacco Ltd) was filed in B.C. courts in 2003, asking the court to consider that Imperial Tobacco had not met its duties under B.C.'s Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act, and seeking compensation for smokers who had been misled into thinking that light cigarettes were less harmful. Thaw lawsuit also asked the court for a permanent injunction against the use of these terms.

The Quebec tobacco class actions (Létourneau and Blais/CQTS) claimed that tobacco companies had not met their obligations under that province's Consumer Protection Act, and both the Quebec Superior Court and the Quebec Court of Appeal agreed. These rulings gave considerable guidance about what standard of behaviour is required from manufacturers of such products, some of which are pasted below. They ordered the companies to pay billions of dollars in compensation, but did not order them to change any current practices. (They were not asked to).

Vaping:

One class action has been filed against JUUL in British Columbia, claiming that the company made false representations about the safety of their products and failed to warn about the risks of their products in ways that went against that province's Business Practices and Consumer Protection Act. In addition to asking for compensation for injuries, the class action is also asking the courts to require that JUUL change its marketing practices. (Other class actions may be in the works).

|

| Class action against JUUL filed in B.C. |

The Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act and its impact on vaping lawsuits

Currently, governments and consumers are able to file lawsuits against JUUL and BLU and minor brands of devices like STLTH and MYLE, but are not permitted to ask courts to block misleading marketing practices by prominent vaping marketers VYPE and LOGIC.

That's because the major tobacco companies that manufacture those brands have, since March of last year, been under insolvency protection using the federal Companies' Creditors Arrangement Act (CCAA). The court has ordered a "stay of proceedings" meaning that " no proceeding or enforcement process in any court or tribunal ... shall be commenced, continued or take place." As long as this order is in place, the companies have a time-out on any further lawsuits against them. (A background note on these proceedings can be found here).

The tobacco companies requested this protection to buy time to negotiate a settlement with the provincial governments that are suing them to recover the costs of treating tobacco-related diseases. These provincial claims are, like the Quebec class actions, largely based on the companies wrongful behaviour in failing to warn and misleading consumers about the harmfulness of their products.

This Thursday (February 20th), the companies are seeking another 6 month extension on their protection from any legal actions against them. Each of the provinces, as well as representatives of injured smokers and other creditors, will have an opportunity to suggest to the court ways that the "stay of proceedings" could be reworded to ensure that governments have clear authority to use the courts to protect the public from the types of wrongful behaviour which put the companies into insolvency. They could also object to the companies' ability to spend hundreds of millions to promote their products (including on ads which oppose government regulation) during the CCAA proceedings.

So far, none of them have indicated they will do so.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Guidance from Quebec Courts on tobacco manufacturers' duties to warn and on misleading tobacco advertising

From Justice Riordan's ruling:

Misleading and non-misleading ads

[535] As a general rule, the ads contain a theme and sub-message of elegance, adventure, independence, romance or sport. As well, they use attractive, healthy-looking models and healthy-looking environments, as seen in the following exhibits ... [incl. 40479]

|

| Left: Neutral and not misleading ad (Ex. 40480) Right: Misleading ad (Ex 40479) |

Duty to warn

[227] Our review of the case law and doctrine applicable in Quebec leads us to the following conclusions as to the scope of a manufacturer's duty to warn in the context of article 1468 and following:

A. The duty to warn "serves to correct the knowledge imbalance between manufacturers and consumers by alerting consumers to any dangers and allowing them to make informed decisions concerning the safe use of the product;

B. A manufacturer knows or is presumed to know the risks and dangers created by its product, as well as any manufacturing defects from which it may suffer;

C. The manufacturer is presumed to know more about the risks of using its products than is the consumer;

D. The consumer relies on the manufacturer for information about safety defects;

E. It is not enough for a manufacturer to respect regulations governing information in the case of a dangerous product;

F. The intensity of the duty to inform varies according to the circumstances, the nature of the product and the level of knowledge of the purchaser and the degree of danger in a product's use; the graver the danger the higher the duty to inform;

G. Manufacturers of products to be ingested or consumed in the human body have a higher duty to inform;

H. Where the ordinary use of a product brings a risk of danger, a general warning is not sufficient; the warning must be sufficiently detailed to give the consumer a full indication of each of the specific dangers arising from the use of the product;

I. The manufacturer's knowledge that its product has caused bodily damage in other cases triggers the principle of precaution whereby it should warn of that possibility;

J. The obligation to inform includes the duty not to give false information; in this area, both acts and omissions may amount to fault; and

K. The obligation to inform includes the duty to provide instructions as to how to use the product so as to avoid or minimize risk.