- Cochrane establishes that in clinical trials, E-cigarettes fail 10 times more often than they succeed (roughly the same as NRT). Other reviews have shown that in real life they are even less successful.

- The products used in the studies reviewed by Cochrane are different than those on the market in Canada. The U.S. Surgeon General recommends that because of the wide variation in products and usage it is not prudent to draw generalized conclusions about their efficacy as stop-smoking medications

- Cochrane reviews show that other stop-smoking medications do better in clinical trials. (The ones that, unlike e-cigarettes, have been assessed and authorized on the basis of their safety, efficacy and quality.)

- Any advice to a smoker to use e-cigarettes to quit smoking (or to reduce the harms from continued nicotine use) should be tailored to individual circumstances and be individually delivered in a therapeutic context. Population-level encouragements for smokers to use e-cigarettes are imprudent. To date these have back-fired in Canada, resulting in more new nicotine addicts than former smokers.

The reviewers memorably present their conclusions in a plain language summary: "For every 100 people using nicotine e‐cigarettes to stop smoking, 9 to 14 might successfully stop, compared with only 6 of 100 people using nicotine‐replacement therapy, 7 of 100 using e‐cigarettes without nicotine, or 4 of 100 people having no support or behavioural support only."

Rather than confirm the superiority of e-cigarettes, these numbers confirm the inadequacy of both vaping products and NRT - even under the best of supervised therapeutic circumstances.

The Cochrane report on e-cigarettes concluded in effect that 90 of 100 smokers who use e-cigarettes to quit smoking will be smoking again within 6 months, compared with 94 failures for every 100 who use NRT.

The relative risk for success between E-cigarettes and NRT is 1.63 (10 vs 6 successes per 100 tries). The relative risk for failure between NRT and E-cigarettes is 1.04 (94 vs 90 failures per 100 tries)

(Simon Chapman provides a good discussion of the high rate of failure in his blog "Would you take a drug that failed with 90% of users? New Cochrane data on vaping “success”)

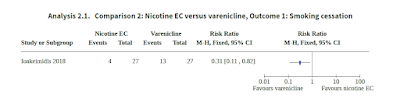

Cochrane has confirmed that in clinical trials, other stop-smoking medications available in Canada do better than e-cigarettes.

Other Cochrane reviews have assessed the effectiveness of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation. These include the stop-smoking medications that have been approved by Health Canada following a review of their safety, efficacy and quality. (The safety, efficacy and quality of e-cigarettes is not examined by Health Canada before they are permitted for sale).

Among these medications are prescription medications Varenicline and Bupropion. These drugs do not replace nicotine from tobacco, but instead help the smoker end nicotine addiction by altering the brain's response to it. Varenicline reduces nicotine withdrawal symptoms and diminishes the rewarding effects of cigarettes. Through a different mechanism, Bupropion also decreases nicotine withdrawal symptoms and may diminish the rewarding effects of cigarettes. Other over-the-counter stop-smoking medications authorized for sale include the natural health product Cytisine and the prescription anti-depressant Nortriptyline.

A 2020 review by Cochrane looked at the effectiveness of some pharmacotherapies, using similar analytic methods to thsoe used in the review on e-cigarettes. This review pharmacotherapies concluded that for every 100 people who tried to quit smoking:

- 17 to 20 were successful at quitting for at least 6 months if they used Bupropion alone (80 to 83 failed).

- 17 to 28 were successful if they used Bupropion and NRT (72 to 83 failed).

- 21 were successful if they used Varenicline alone (79 failed).

- 20 to 33 were successful if they used Varenicline and Bupropion (67 to 80 failed).

- An Australian review of RCT's found limited evidence that in the clinical setting freebase nicotine e-cigarettes are efficacious as an aid to smoking, and that they double the likelihood of relapse to resuming smoking, strong evidence that e-cigarettes increase combustible smoking uptake in non-smokers, and insufficient evidence that nicotine e-cigarettes are efficacious outside the clinical setting. (Banks et al, 2022)

- An Irish review of RCT's found "no clear evidence of a difference of effect" between e-cigarettes and NRT. (Quigley et al. 2021)

- A review for the US Preventive Services Task Force found "inconsistent" results in RCT's and did not conclude that e-cigarettes were effective as a therapeutic product for smoking cessation. (Patnode et al, 2021)

- The U.S. Surgeon General found that there was too much variation in the products sold and the way they were used to make generalizations about whether or not they were effective for smoking cessation. (U.S. Surgeon General, 2020).

- Swedish review of RCT's and longitudinal studies found no net benefit to the use of e-cigarettes for quitting smoking was found. (Hedman et al, 2021)

- American researchers looking at RCT's and observational studies found that although e-cigarettes were found to be effective when used as therapeutic interventions in clinical settings, this was not the case when they were sold as consumer products in the general population. (Wang et al, 2021).

- Analysis of American smokers over time found no evidence that higher nicotine e-cigarettes (or lower nicotine cigarettes) improved successful quitting or prevented relapse (Chen et al, 2022)

- Another study using the same longitudinal study found that dual users were less likely to quit. (Osibogun et al, 2022)

- * A study conducted by Environics for Health Canada, which followed vapers over a two-year period finding no net reduction in smoking (Environics POR 113-20)

There are a number of aspects of e-cigarette use that were not included in the Cochrane assessment, and harms which were not accepted as "adverse consequences". These include:

- the increased health risks incurred by smokers who try e-cigarettes, but continue to smoke (dual users), thereby inhaling the different harmful chemicals in each type of product.

- the increased health risks incurred by smokers who successfully quit with e-cigarettes, but who continue to use them. (The Hajek research found that those who successfully quit using NRT are half as likely to continue using nicotine as those who used e-cigarettes).

- the initiation into nicotine use by young people who are influenced by messaging that encourages e-cigarette use.

- the role of the tobacco industry in designing and supplying both cigarettes and e-cigarettes, and the commercial pressure that encourages them to market these in ways which maintain sales.

The impact of this policy change is reflected in federal surveys, which show that the uptake of these products was largely among young people, and not among adult smokers.